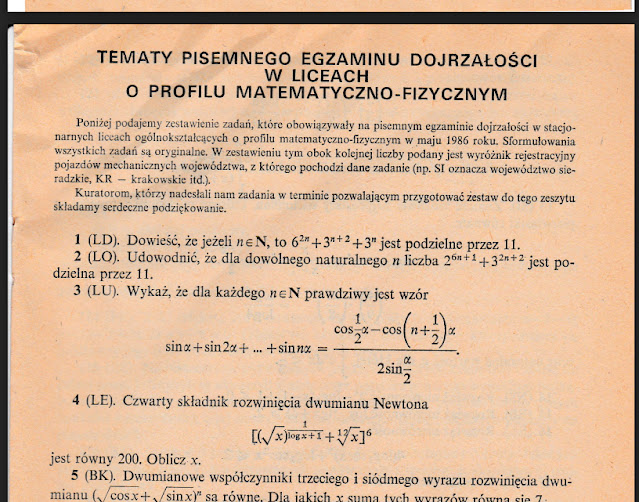

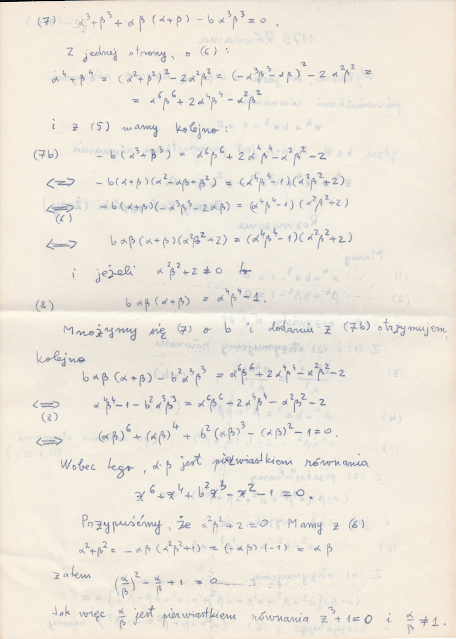

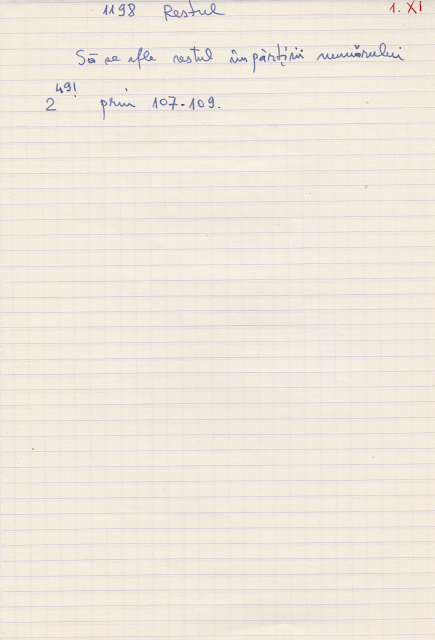

It is Problem 1 from the column "Topics of the written maturity examination in high schools with a mathematical and physical profile", in the magazine MATHEMATYKA, No. 6/1986, page 363.

In translate, thanks to Mr. DeepL:

"Prove that if $n \in \mathbb{N}$, then $6^{2n}+3^{n+2}+3^n$ is divisible by $11$."

We will note $a \mid b$ if the number $a$ divides the number $b$, respectively $b\; \vdots \; a$ the equivalent statement that the number $b$ is divisible by the number $a$.

SOLUTION 1 CiP

Solution by Mathematical Induction. Let $c_n \overset{def}{=}6^{2n}+3^{n+2}+3^n$.

For $n=0,\;c_0=6^0+3^2+3^0=11$, so $c_0 \;\vdots \;11$.

We assume the statement true for $n=k,\;c_k \;\vdots \;11$. Then

$$c_{k+1}=6^{2(k+1)}=3^{(k+1)+2}+3^{k+1}=6^{2k+2}+3^{k+3}+3^{k+1}=6^{2k}\cdot 36+3^{k+3}+3^{k+1}=$$

$$=3(12 \cdot 6^{2k}+3^{k+2}+3^k)\;\underset{3^{k+2}+3^k=c_k-6^{2k}}{=}\;3(12\cdot 6^{2k}+c_k-6^{2k})=$$

$$=3(11\cdot 6^{2k}+c_k)\;\;\vdots\;\;11,$$

because in parenthesis all terms are divisible by $11$. So the statement is also true for $n=k+1$.

By Mathematical_Induction, the statement is true for all $n\in \mathbb{N}.$

$\blacksquare$

SOLUTION 2 CiP

We write the given expression successively

$$6^{2n}+3^{n+2}+3^n=$$

$$=2^{2n}\cdot 3^{2n}+3^{n+2}+3^n=3^n\cdot(2^{2n}\cdot 3^n+3^2+1)=3^n(4^n\cdot 3^n+10)=$$

$$=3^n({12}^n+10)=3^n[(11+1)^n+10]=3^n[(11\cdot d +1)+10]=3^n(d+1)\cdot 11\;\vdots\;11.$$

We used that, in developing $(11+1)^n$ with Newton's binomial formula, the terms, except the last one which are $1^n$, are divisible by $11$.

$\blacksquare \;\blacksquare$

REMARKS

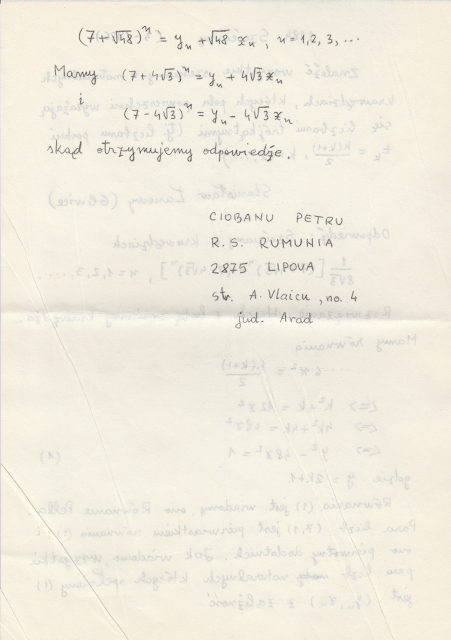

$1^R.$ We see in the image that Problem 2 is of the same kind.

Directly, using the formula $(a+b)^n=a\cdot d+b^n$, we have

$$c_n\;\overset{def}{=}2^{6n+1}+3^{2n+2}=2\cdot {64}^n+9 \cdot 9^n=2\cdot(66-2)^n+9\cdot (11-2)^n=$$

$$=2(66\cdot d_1+(-2)^n)+9(11\cdot d_2+(-2)^n)=11\cdot (12d_1+9d_2)+2\cdot (-2)^n+9 \cdot (-2)^n=$$

$$=11d_3+11 \cdot (-2)^n\;\;\vdots \;11.$$

In another way, through Mathematical Induction as in Solution 1, we can use the formulas

$$c_{n+1}=2^{6n+7}+3^{2n+4}=64 \cdot 2^{6n+1}+9\cdot3^{2n+2}=64c_n-55\cdot 3^{2n+2},$$

or,

$$c_{n+1}=9c_n+55\cdot 2^{6n+1}$$

whence we see that $c_n\;\vdots 11\;\;\Rightarrow \;c_{n+1}\;\vdots 11.$

end Rem. 1

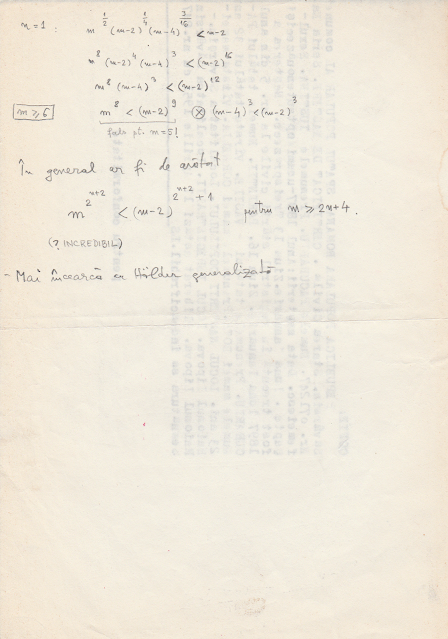

$2^R.$ The numbers in Problem 1 are in fact $6^{2n}+10\cdot 3^n$ so we have a whole class of problems of the type

$$\alpha \cdot a^{k\cdot n}+\beta \cdot b^{l\cdot n}\;\vdots \;p. \tag{1}$$

We just have to find suitable integers $\alpha, \beta \in \mathbb{Z},\;k,l \in \mathbb{N}$ and (possibly prime) $p$ so that $(1)$ is true for any $n\in \mathbb{N}$.

end Rem. 2