It seems that the Mathematical Olympiad has begun.

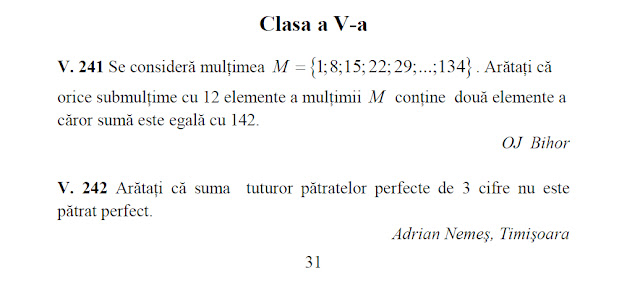

Let's try to put ourselves in the shoes of a 5th grader. Let's take a list of issues given not too long ago. For example, let's consult the magazine below.

We will choose three 5th grade problems from the first stage of the Olympiad as examples.

Problem 1 (at page 1) "A test has 20 questions, which are to be solved in 150

minutes. The questions are of three types: easy, medium and difficult.

It is expected that each of the 7 easy questions can be solved in 4

minutes and each of the medium questions can be solved in 8 minutes.

How many minutes are left for solving difficult questions?"

A. 56 B. 58 C.62 D. 66 E. 70

Answer CiP D. 66

Solution CiP

Easy questions and medium questions require a solving time of $7 \cdot 4+7\cdot 8=24$ minutes. So for the difficult questions, $150-84=66$ minutes remain. The answer is D.

$\blacksquare$

Remark CiP We have 7 easy questions and 7 medium questions, so the number of difficult questions is $20-7-7=6$. So each difficult question is expected to be solved in 11 minutes.

< end Rem>

In light of the statement in Problem 1, it seems that Problems 1-7 are considered easy, Problems 8-14 are medium, and Problems 15-20 are difficult. I will take one of each.

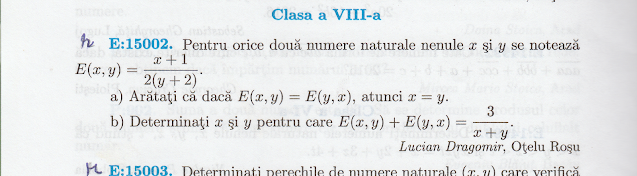

I also mention that the Magazine in the image above does not contain the corresponding answers to these questions. Despite the other qualities: e.g. a clear English that would make even Shakespeare envious. News about the adventures at this Olympics also appeared in the press. That's also where I found out where you can find the Answers. The same lovely SSMR.

Problem 11 (at page 2) "The largest integer which divided by 2022 gives a

quotient smaller than the remainder is :

A. 1048043482 B. 4086461 C. 16185 D. 8091 E. 9 "

Answer CiP B. 4086461

Solution CiP

By dividing a number $D$ by $2022$ we obtain the quotient $Q$ and the remainder $R$, according to the long division as below

$$\begin{array}{c|c} D & 2022 \\ \hline \vdots & Q \\ \hline R & \; \end{array}$$

and the Division with remainder Theorem is written

$$D=2022\cdot Q+R\;\; \quad R<2022 \tag{1}$$

The statement also specifies the condition

$$Q\;<\;R \tag{2}$$

So the first relation (1) gives us $D<2022R+R$ , or $D<2023R$. But from the second relation (1) we have $D\leqslant 2021$, and so

$$D<2023 \cdot 2021 =4\;088\; 483.$$

So the answer "A." is excluded, being a larger number.

We see from (1) that the largest admissible number $D$ occurs when $R$ and $Q$ are the largest, also verifying the condition (2), so

$$Q=R-1=2020.$$

Hence $D=2022 \cdot 2020+2021=4\;086\;461$, so answer is B.

$\blacksquare$

Remark CiP Answer options C and E also verify the condition (2)

$$16\;185 \;:\;2022 \;=\;8\quad remainder\;9\;\quad \quad 9\;:\;2022\;=\;0\quad remainer\;9$$

but option D does not $8\;091\;;\;2022\;=\;4\quad remainder\;3.$

<end Rem>

Problem 18 (at page 3) "If $S(n)$ denotes the sum of the digits of the number

$n$, then the number of $n-$s so that $\;2021\leqslant n+S(n)\leqslant 2022$ is:

A. 0 B. 1 C. 2 D. 3 E. 4 "

Answer CiP C. 2

$$1996+S(1996)=1996+25=2021\;\quad \; 2014+S(2014)=2014+7=2021$$

Solution CiP

$n=0$ does not satisfy the condition.

If $n\leqslant 1999$ we have $S(n)\leqslant 28$, and then

$$n\geqslant 2021-S(n)\geqslant 2021-28=1993.$$

We have to try the numbers:

$$1993,\quad 1994,\quad\cdots,1999.\quad \tag{1}$$

After some calculations:

$$1993+S(1993)=1993+22=2015,$$

$$1994+S(1994)=1994+23=2017,$$

$$1995+S(1995)=1995+24=2019,$$

$1996+S(1996)=1996+25=2021$ - this number is convenient

we see that for the other numbers in the list (1) the value $n+S(n)$ exceeds 2023.

If $n\geqslant 2000$ (anyway $n\leqslant 2022$) we have $S(n)\geqslant 2$ so

$n\leqslant 2022-S(n)\leqslant 2020$.

Among the numbers 2000, 2001, ..2020 the highest $S(n)$ value is $S(2019)=12$ and then, from $n\geqslant 2021-S(n)$ we get $n\geqslant 2021-12=2009$, so we have to try only the numbers

$$2009,\quad 2010,\;\dots\;2020.\quad \tag{2}$$

Observing the evolution of calculations:

$$2009+S(2009)=2009+11=2020$$

$$2010+S(2010)=2010+3=2013$$

$$2011+S(2011)=2011+4=2015$$

$$2012+S(2012)=2012+5=2017$$

$$2013+S(2013)=2013+6=2019$$

$2014+S(2014)=2014+7=2021$ - this number is convenient

$$2015+S(2015)=2015+8=2023$$

it turns out that from here on out, there can be no more convenient numbers in list (2).

$\blacksquare$